Open Sourcing Ourselves

“Open Sourcing Ourselves” is a keynote talk I gave at the 2017 Bioinformatics Open Source Conference (BOSC) on August 22. The talk reflects on a bit of my own history, my experiences with the Personal Genome Project, my vision for Open Humans, and how we – as humans – can open source ourselves.

The talk is 39 minutes in length, and a written transcript of it is below.

Thank you. I’m honored and thrilled to have a chance to speak with you today, and to tell you about my vision for how we can open source ourselves. In addition to my current work on Open Humans, I was previously Director of Research at the Personal Genome Project.

So… I thought I’d get started on how I got here, and got interested in sharing.

It all started with me discovering something wrong on the Internet.

It all started with me discovering something wrong on the Internet.

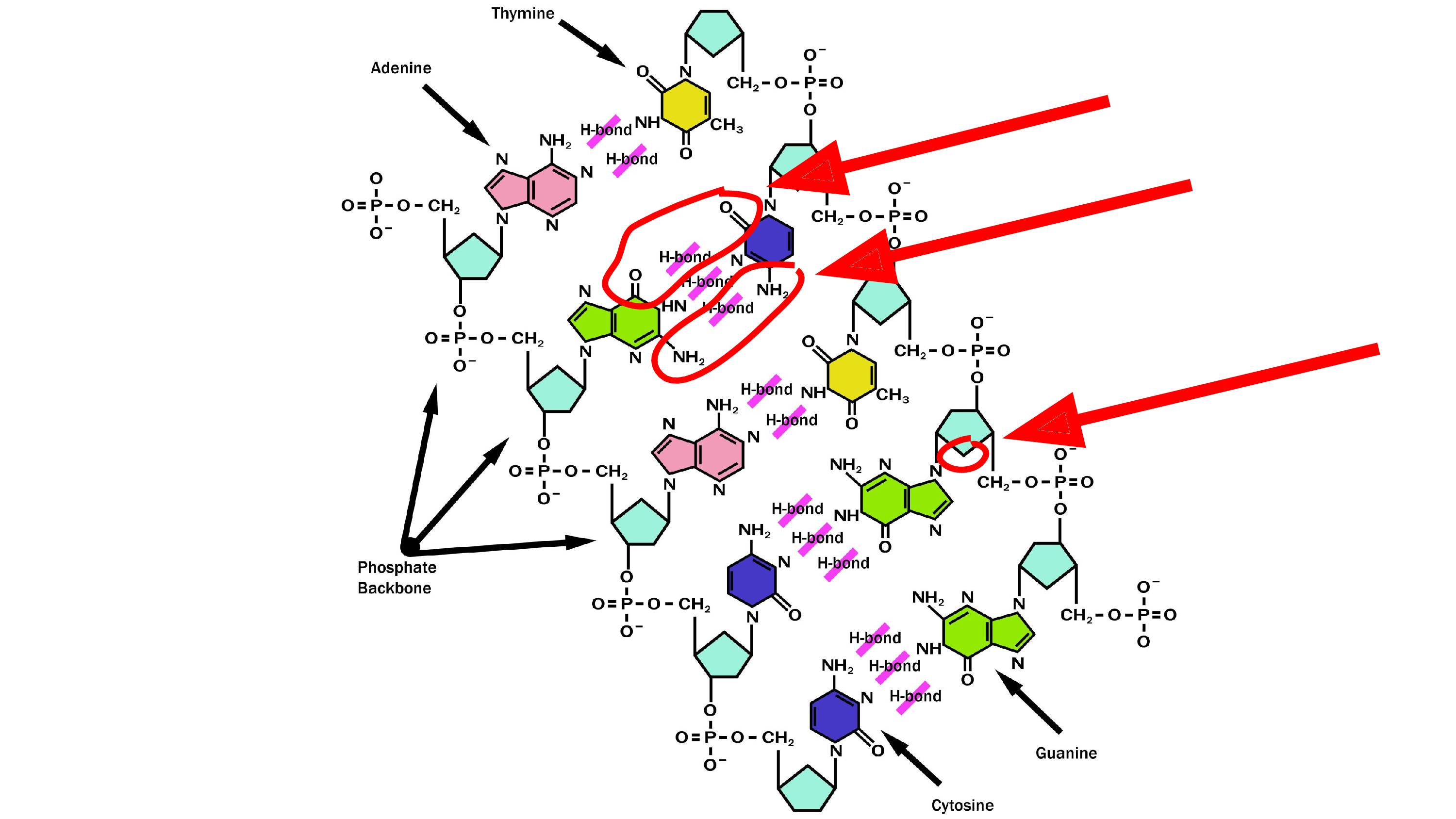

I needed a picture of DNA for a slide during my lab meeting presentation, and it was only later that I discovered that this picture – which I took from the DNA Wikipedia page – is wrong. That’s not how hydrogen bonds work! The oxygen does not bond to oxygen, and there’s a missing oxygen in the ribose. These are the parts that are wrong. So I had to fix that.

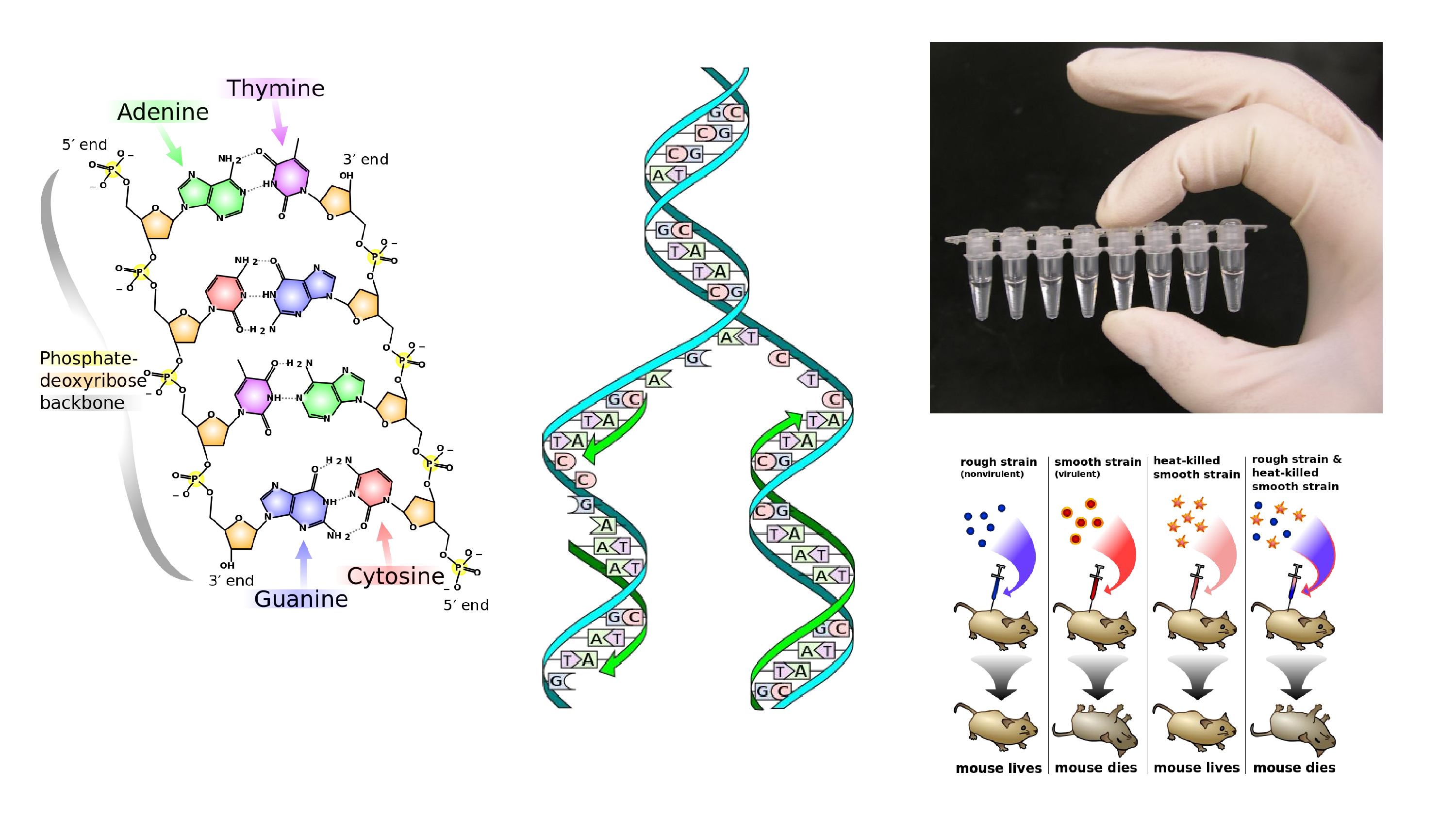

I created a new version of that picture to go on to the DNA page. And I took it from there. It turns out that replication forks are kind of easy to mess up, so that one was fixed. There’s the Griffith’s Experiment, the history of genetics. And in the top right is a picture of some PCR tubes. That’s my hand at the top of the PCR page. That’s immortality.

I created a new version of that picture to go on to the DNA page. And I took it from there. It turns out that replication forks are kind of easy to mess up, so that one was fixed. There’s the Griffith’s Experiment, the history of genetics. And in the top right is a picture of some PCR tubes. That’s my hand at the top of the PCR page. That’s immortality.

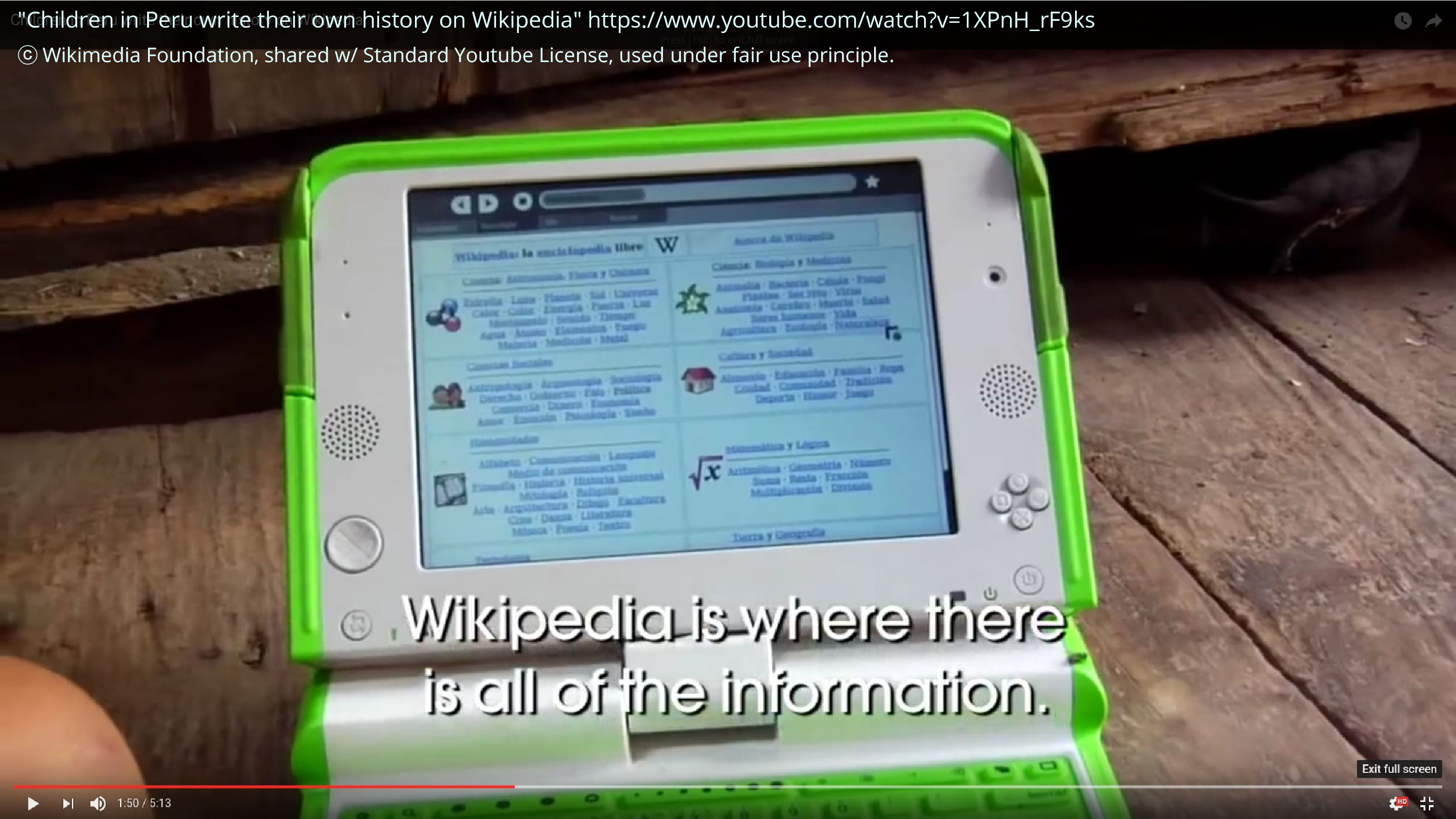

I also had the opportunity to do some stuff that felt really meaningful. I worked with One Laptop Per Child to put together a bunch of articles for an offline Wikipedia that was then used by hundreds of thousands of children in Peru and Uruguay. And this is a screencap from a YouTube video on this. And sometimes it feels wonderful to be able to empower people, by giving them things, simple things like knowledge that we take for granted.

I also had the opportunity to do some stuff that felt really meaningful. I worked with One Laptop Per Child to put together a bunch of articles for an offline Wikipedia that was then used by hundreds of thousands of children in Peru and Uruguay. And this is a screencap from a YouTube video on this. And sometimes it feels wonderful to be able to empower people, by giving them things, simple things like knowledge that we take for granted.

Importantly, I also added no less than three pictures of cats to Wikipedia pages. The middle one is one of my favorite demonstrations of mutations, it’s a temperature-sensitive mutation. I also brought the Genetics article to Featured Article status.

Importantly, I also added no less than three pictures of cats to Wikipedia pages. The middle one is one of my favorite demonstrations of mutations, it’s a temperature-sensitive mutation. I also brought the Genetics article to Featured Article status.

And I learned that sharing feels good. In the top right there’s a “barnstar”, that’s the way that Wikipedians reward each other for good work. I got a physical one from my friend Kat Walsh, who was really into Wikipedia at the time. She’s actually now one of the board members of the Free Software Foundation. It all connects.

I also come away from my work with Wikipedia with this sense that open systems can win, and Wikipedia is this open system for sharing knowledge that was previously in closed encyclopedias.

In the meantime, I was being a graduate student. I was doing biotech development in George Church’s lab. I was developing a method for doing cytosine methylation profiling using methylation-sensitive restriction enzymes – these pictures are not here to teach you anything – it’s just proof that I was at the bench, and then I took that data – I actually worked with some of the early sequencing machines, and then gave up and used Illumina – and did programming, used software, used Python to analyze the data and create graphics and what-not.

As I wrapped up that work, I discovered something else in the lab that caught my attention – that was about sharing. And that was George’s vision for a sort of radical sense of sharing, called the Personal Genome Project.

George’s vision was grand. It was big. He wanted to open source our genomes, make them public domain, in combination with extensive phenotype data. And here I’ve taken a quote from his original proposal: “full medical records”, “craniofacial MRI”. He wanted the data that was potentially identifiable, and in full public data release. He wanted people to enter into this, with the exposure of themselves, agreeing to the potential of re-identification. Or potentially simply identifying themselves, and donating all of this information into the public good.

George’s vision was grand. It was big. He wanted to open source our genomes, make them public domain, in combination with extensive phenotype data. And here I’ve taken a quote from his original proposal: “full medical records”, “craniofacial MRI”. He wanted the data that was potentially identifiable, and in full public data release. He wanted people to enter into this, with the exposure of themselves, agreeing to the potential of re-identification. Or potentially simply identifying themselves, and donating all of this information into the public good.

So this is a sort of literal sense of “open sourcing ourselves”.

There’s actually Personal Genome Projects in other places, in the UK, and Austria, and Canada – and one of the UK PGP folks is here. But at the pilot site at Harvard, with George Church, I was the Director of Research for several years, and I was a de facto project manager. I was working in every aspect of the project, from soup to nuts: from collecting the samples to analyzing the output data and talking to participants.

In the end, in its current state this project has produced 351 participant genomes, and there’s over 1900 phenotype surveys – traits – and I would say this is not a super impressive amount of data compared to the vast amount of data that is being produced and shared and you’re all working with. So I’m not going to claim that there’s a particularly impactful amount of data in that, but the PGP’s biggest impact was probably the ELSI stuff: the Ethical, Legal and Societal Implications. Because it was really pushing boundaries on what we considered was shareable, and what are the risks participants can agree to take, when they choose to share. It’s impressive that the IRB agreed to let the study proceed – there are IRBs that I’ve since engaged with that are far more conservative.

So I’m going to give you some of my takeaway lessons from working with the Personal Genome Project.

One is engaging participants and sharing with them.

One is engaging participants and sharing with them.

The Personal Genome Project was a highly engaged project, as we were producing this data, which is unusual – most projects will take a sample and then maybe get back to you much later, but there was an ongoing relationship formed with these participants and they talked to us about a lot of things. This is a picture from our GET Conference, which Jason Bobe, in the foreground, organized – he’s the former Executive Director of the organization that I now lead. And that’s one of our outstanding participants, James Turner, his name may come up again later, he’s just a great contributor to the community in addition to sharing his data.

One of the things we did as part of this engagement was returning data. Almost nobody does this: almost nobody did this, and almost nobody does this right now. Most of the genomes we are producing are not shared with the individuals they come from. As researchers, I think we might look to what the commercial companies are doing – where it’s easy to download your genetic data – and ask ourselves the hard question of whether we are performing data sharing with the participants that it came from. We talk a lot about sharing the data with each other.

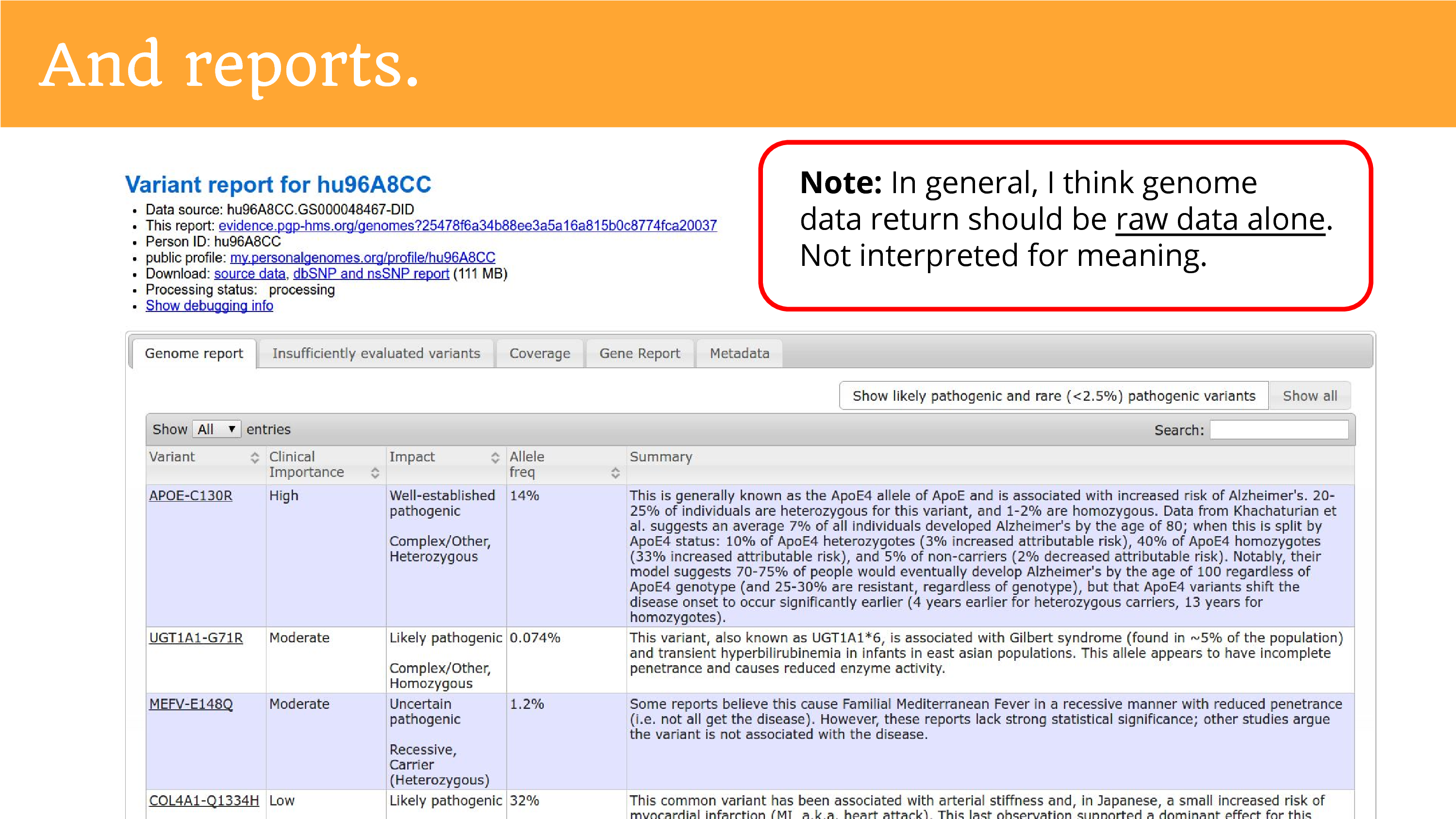

When we returned the genome data, we also had to do reports. This is part of trying to give people insight into what it is they’re trying to share. And the truth is that we don’t really understand everything in the genome, so we just tried our best and told them it was a preliminary report, but hopefully they’re okay to go ahead from there. I want to make a note – I think this is conflated a lot in conversations about returning genomes – I don’t think most groups returning data need to engage in this. It was a special activity for the Personal Genome Project because the ask for public data release sort of brought the obligation to help people try to understand the data. The act of interpretation is far more burdensome than the raw data alone, and it brings you close to that position of being a clinician and explaining things to people, that researchers should not have to be in.

When we returned the genome data, we also had to do reports. This is part of trying to give people insight into what it is they’re trying to share. And the truth is that we don’t really understand everything in the genome, so we just tried our best and told them it was a preliminary report, but hopefully they’re okay to go ahead from there. I want to make a note – I think this is conflated a lot in conversations about returning genomes – I don’t think most groups returning data need to engage in this. It was a special activity for the Personal Genome Project because the ask for public data release sort of brought the obligation to help people try to understand the data. The act of interpretation is far more burdensome than the raw data alone, and it brings you close to that position of being a clinician and explaining things to people, that researchers should not have to be in.

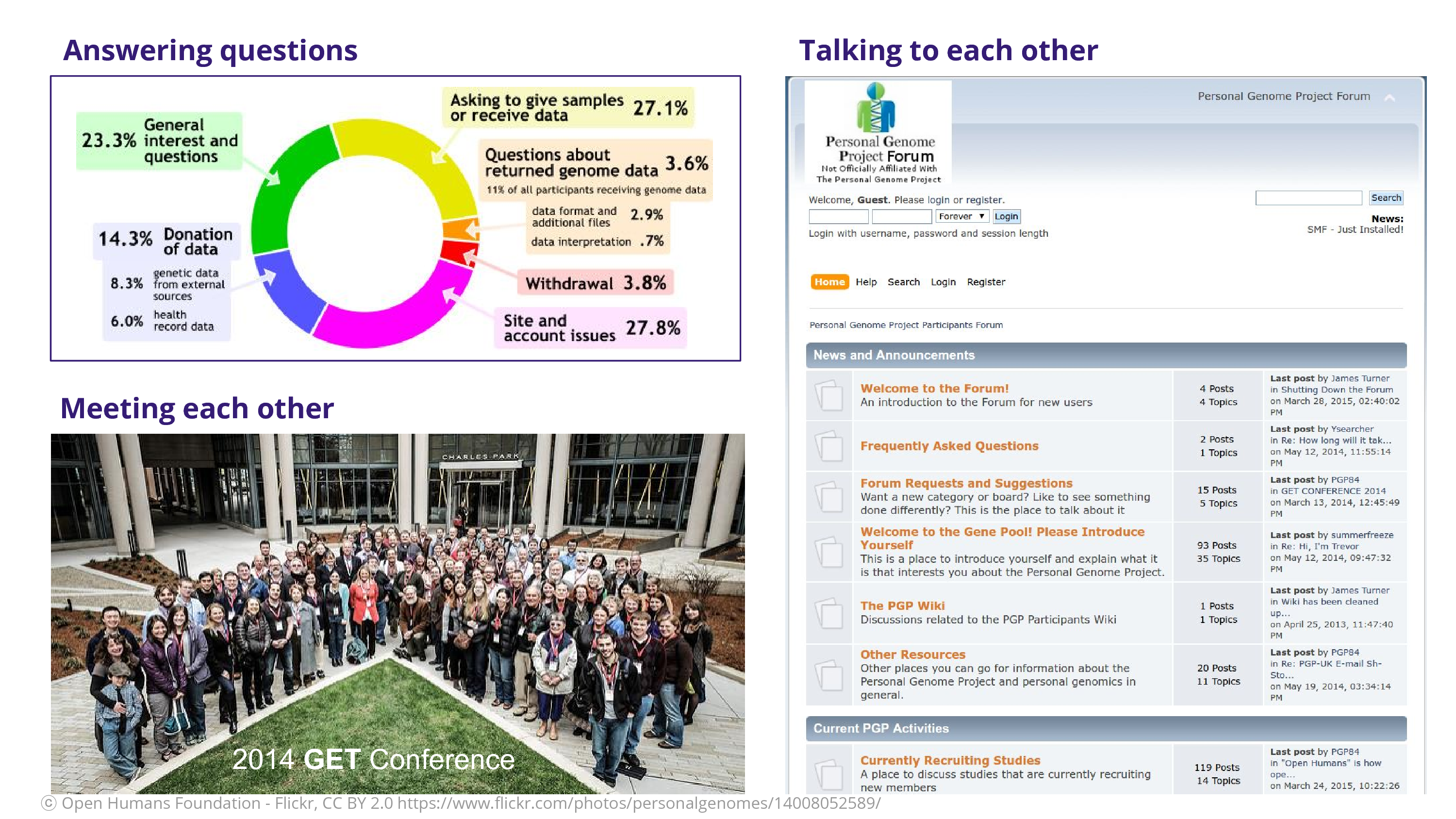

I found myself answering lots of questions: a lot of the questions were about how to donate data or give samples. They wanted to be involved in the project. Not so many were concerned about the data that they received, which is a relief, because I think a lot of our fears around engaging the participants are if they’re going to keep asking us questions. There was meeting each other at these GET Conferences, where we got a lot of time to meet the participants themselves. And finally – and kind of radically – participants were able to talk to each other. Think about a classic research study where someone comes in and you get the sample and then they’re gone. They’re not talking to each other as participants! They don’t have that ability to complain about you by talking to each other. Ceding that power to the participant is, I think, a scary act but a wonderful act. It acknowledges them as co-creators in the project of science.

I found myself answering lots of questions: a lot of the questions were about how to donate data or give samples. They wanted to be involved in the project. Not so many were concerned about the data that they received, which is a relief, because I think a lot of our fears around engaging the participants are if they’re going to keep asking us questions. There was meeting each other at these GET Conferences, where we got a lot of time to meet the participants themselves. And finally – and kind of radically – participants were able to talk to each other. Think about a classic research study where someone comes in and you get the sample and then they’re gone. They’re not talking to each other as participants! They don’t have that ability to complain about you by talking to each other. Ceding that power to the participant is, I think, a scary act but a wonderful act. It acknowledges them as co-creators in the project of science.

That’s a forum that James Turner, a participant, put together. A participant put together this forum so that participants could talk to each other.

So, to wrap that section up a bit, here’s some participant engagement tips. I’m guessing none of you engage participants… but if you ever consider it… here’s my tips.

So, to wrap that section up a bit, here’s some participant engagement tips. I’m guessing none of you engage participants… but if you ever consider it… here’s my tips.

Help a bit, but then point them to other resources. And set expectations. The temptation of someone who’s never done this is to get sucked into the explaining, to give them so much support, because you have so much knowledge. You just want to give it all to them.

Develop standard responses, so you’re not like typing out a new response each time, but you just kind of have a standard one that works for a lot of things.

But, you know, for all those limitations you should always be extremely thankful. Wrap up with a thank you, start with a thank you. Because your research would not exist without them. And often participation in research is a lot more work than you think it is, when you’re receiving their samples or their data. Participants can go to a lot of effort just to be part of the study.

The second topic is to bring the elephant into the room, and to talk about scary data. And this is probably the most interesting topic for people here, because we worry about privacy when we talk about data from humans. Genome data and other omics data. And yet there are individuals who still choose to share.

The second topic is to bring the elephant into the room, and to talk about scary data. And this is probably the most interesting topic for people here, because we worry about privacy when we talk about data from humans. Genome data and other omics data. And yet there are individuals who still choose to share.

Well I feel like I learned lessons from genomes. A lot of this conversation around genomes treats it like this mystical object, like it’s a special type of data, but the truth is there’s a lot of data about ourselves that has these properties. With genomes we have this ability to discover meaningful information, and potentially re-identify.

The meaningful information that we usually think about first, as researchers in biology, is that biological information – the traits, the medical effects, the diseases. Some of it is innocuous in the sense that you’re not going to care if someone finds out you’re a carrier for a recessive disease. I’m a carrier for a recessive disease, for microcephaly. So, we all are. It’s not a big deal.

The meaningful information that we usually think about first, as researchers in biology, is that biological information – the traits, the medical effects, the diseases. Some of it is innocuous in the sense that you’re not going to care if someone finds out you’re a carrier for a recessive disease. I’m a carrier for a recessive disease, for microcephaly. So, we all are. It’s not a big deal.

But there’s other things that we would hesitate for others to know about. For example, an ApoE4 allele – or, say you have two – those are more unusual, but there’s probably people in this room that have two E4 alleles, and that greatly increases your risk of Alzheimer’s disease. There’s not much to be done about it. And there’s limits to what we can do to protect people from genetic discrimination. You can pass a law that says you should not discriminate, but if you’re, say, the CEO of a publicly traded company… you can’t tell people not to sell their stock. So, there’s limits to our ability to protect people from the consequences of the information getting out. So, it’s valid to be worried.

The other thing that we often forget, that we find in genome data, is ancestry information. And this is actually the most popular reason for people to go out and get their genetic data. There’s more, far more people getting AncestryDNA than 23andMe. This is also a potential source for unexpected discoveries. So, while ancestry can mean stuff like race and ethnicity predictions, it can also mean discovering relatives – like 2nd or 3rd degree cousins – that you had lost track of. Or, perhaps, a half sibling you didn’t know about, due to your father’s affair some decades in the past.

The other thing that we often forget, that we find in genome data, is ancestry information. And this is actually the most popular reason for people to go out and get their genetic data. There’s more, far more people getting AncestryDNA than 23andMe. This is also a potential source for unexpected discoveries. So, while ancestry can mean stuff like race and ethnicity predictions, it can also mean discovering relatives – like 2nd or 3rd degree cousins – that you had lost track of. Or, perhaps, a half sibling you didn’t know about, due to your father’s affair some decades in the past.

So, a lot of the worries around genetic data have centered on the health surprises. But some of the biggest bad stories have come around the family, the ancestry surprises.

Finally, this ancestry information is what is rendering genomes highly identifiable. It turns out that for many people, Y chromosomes and surnames have been inherited in the same way – patrilineally – and there’s ancestry buffs who have created databases that correlate these two. And once you have that, the cat’s out of the bag, and you can start re-identifying genomes. And that’s exactly what was done.

Another reflection on what genomes have meant for us is the fact that cells have genomes too. And we’ve been producing cell lines for decades. And it’s this phenomenon of discovering that you were disseminating data that you thought was safe, and then you discover that it’s not. And we’re always going to struggle with that fear, where we think we’re going to disseminate, we think something’s okay to share – but what if, what if.

Another reflection on what genomes have meant for us is the fact that cells have genomes too. And we’ve been producing cell lines for decades. And it’s this phenomenon of discovering that you were disseminating data that you thought was safe, and then you discover that it’s not. And we’re always going to struggle with that fear, where we think we’re going to disseminate, we think something’s okay to share – but what if, what if.

There’s not a lot of easy answers there, but maybe some lessons to look at. There haven’t actually been people sequencing the cell genomes and then outing people based on them. So maybe humanity on the whole likes to behave pretty well.

So, genomes have taught me broader lessons. I’m now going to introduce you to another type of data that’s kind of like genomes.

This is location data. This is a map of where I was over the course of two years in New York City. So that’s Manhattan on the left, Queens on the right. Most people can be re-identified from location data because they spend most of their time in two places: work and home. And it’s very hard to scrub this data to remove that identifying feature.

This is location data. This is a map of where I was over the course of two years in New York City. So that’s Manhattan on the left, Queens on the right. Most people can be re-identified from location data because they spend most of their time in two places: work and home. And it’s very hard to scrub this data to remove that identifying feature.

In addition I think you can imagine why people would consider location data to be sensitive. They don’t want people to know where they’ve been.

It’s also very valuable for research. Where were you when you engaged in certain behaviors? How do your walking habits in the city vary according to weather or season?

So. One of the lessons from this might be that, for some data, only a few will be “public”. Not everyone is going to want to share their genome, and probably even fewer want to share their location data.

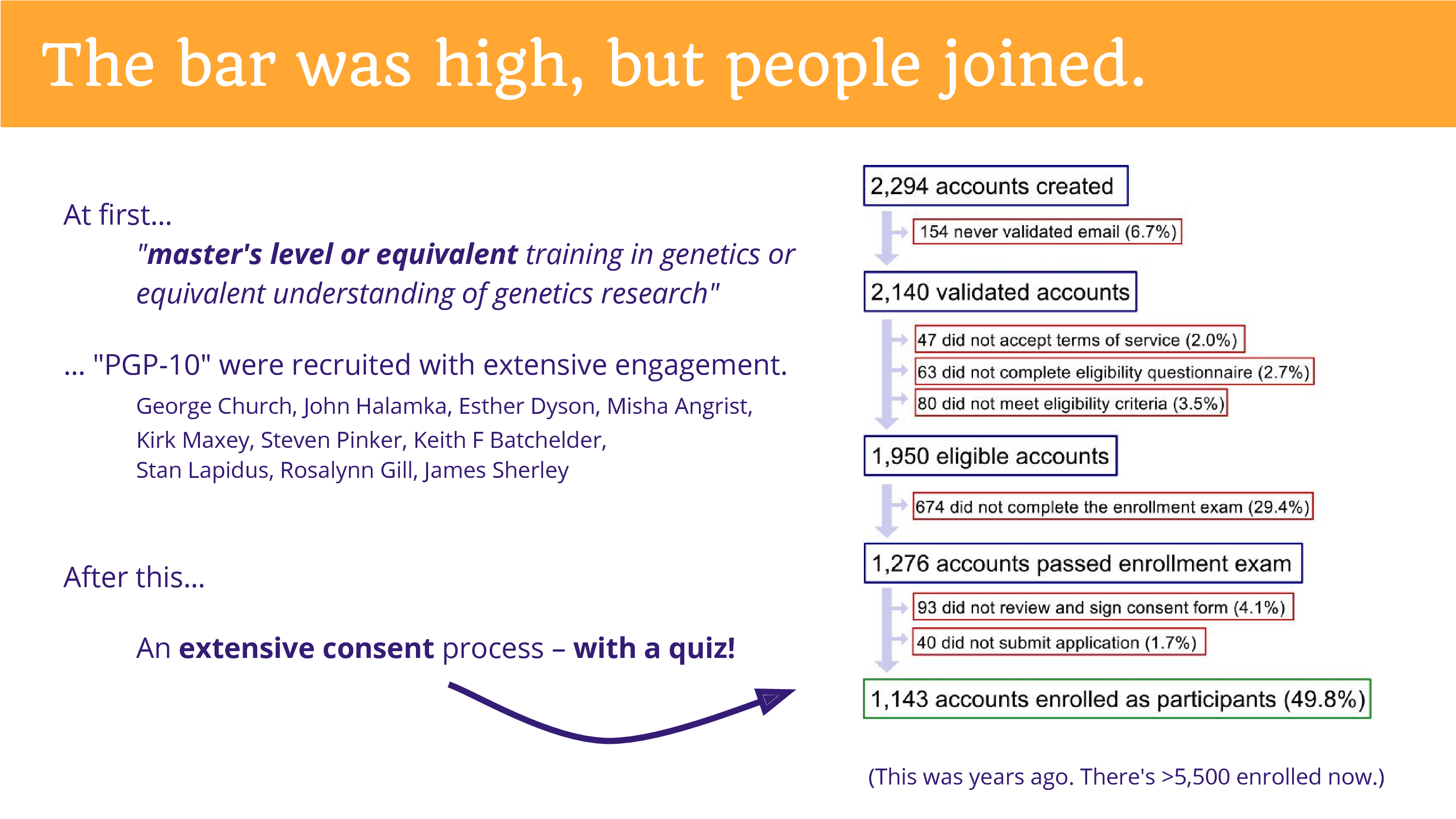

So to get back to the PGP: how did the PGP do this in an ethical manner? How did it choose to engage individuals to publicly share this data? Well, it started out with a high bar: master’s level or equivalent training in genetics. And the first ten participants were recruited with an extensive engagement with the ethics board, and interviews, they were all interviewed to make sure they knew what they were getting into. Although nobody really knows what you’re getting into when you’re doing stuff like this.

So to get back to the PGP: how did the PGP do this in an ethical manner? How did it choose to engage individuals to publicly share this data? Well, it started out with a high bar: master’s level or equivalent training in genetics. And the first ten participants were recruited with an extensive engagement with the ethics board, and interviews, they were all interviewed to make sure they knew what they were getting into. Although nobody really knows what you’re getting into when you’re doing stuff like this.

And after those ten people, the project developed an extensive consent process with a quiz. And I’ve since learned a bit about consent. It’s actually really hard to do consent well, because it’s just like terms of use, you just sign it. You’re not paying a lot of attention. You can try to make plain language, but people are not paying attention. But that quiz that was added does have an effect – and that’s also come out in studies, if you add a quiz suddenly people start understanding stuff – and you can see from this analysis of the enrollment data, that a lot of people dropped out at that quiz stage.

(This is an old analysis. There’s now over 5500 people enrolled, over the intervening years since I did this.)

So in conclusion, people are willing to share. But they like to be asked.

So in conclusion, people are willing to share. But they like to be asked.

There’s over 3500 people – this is my estimate – that have made their genetic data, genotyping or genome data, public domain. If you recall my numbers a little earlier, there wasn’t that many PGP genomes. A lot of these are genotyping data sets donated from direct to consumer companies like 23andMe. Many of them are from the PGP, but actually many more of them are from the OpenSNP project. Bastian’s right there.

So. A third observation on this is how the Personal Genome Project had this sort of hubris of trying to study everything. And that this actually a bit difficult to do.

So. A third observation on this is how the Personal Genome Project had this sort of hubris of trying to study everything. And that this actually a bit difficult to do.

These are some of the projects that I’ve worked with, that did work with Personal Genome Project participants. Some of them to great success. In the top left, the Genome in a Bottle consortium has genomes that are a public reference standard in the United States, that could be used to calibrate your sequencing device. And that’s produced from PGP participants.

It’s complicated though, to engage all of these different groups. One observation here is that at some point, the Personal Genome Project is no longer doing the research. It’s engaging other studies to do the research. And at some point the IRB starts getting confused. I praise the IRB, but they’re people. They’re humans. And having the study coming back with a new engagement plan each time was quite a burden on them, to ethically review and understand what the heck was going on. And that could create some rather dramatic frictions.

It’s complicated though, to engage all of these different groups. One observation here is that at some point, the Personal Genome Project is no longer doing the research. It’s engaging other studies to do the research. And at some point the IRB starts getting confused. I praise the IRB, but they’re people. They’re humans. And having the study coming back with a new engagement plan each time was quite a burden on them, to ethically review and understand what the heck was going on. And that could create some rather dramatic frictions.

And yet, many do dream of comprehensive data. This is a United States program, the Precision Medicine Initiative. It’s impossible for me to talk to people in the United States about PGP or Open Humans without having this come up. Because there’s these features, of wanting to collect data, of many different sources, to do everything, to be data-driven and participant-engaged. Biology, behavior, genetics, environment, data science, computation… it’s just everything, the more you can pack into it, the better. It’s hard.

And yet, many do dream of comprehensive data. This is a United States program, the Precision Medicine Initiative. It’s impossible for me to talk to people in the United States about PGP or Open Humans without having this come up. Because there’s these features, of wanting to collect data, of many different sources, to do everything, to be data-driven and participant-engaged. Biology, behavior, genetics, environment, data science, computation… it’s just everything, the more you can pack into it, the better. It’s hard.

So from those lessons, I came out of it thinking how to improve the underlying design of how this mechanism was working. Iterate and improve. And thinking about a new way to be open about ourselves. Maybe a little bit less simple than the model of making the data public domain.

And that is Open Humans. It is a nonprofit project. It has been supported by funding from these three philanthropic organizations. And it’s really trying to provide something that all of us can benefit from.

And that is Open Humans. It is a nonprofit project. It has been supported by funding from these three philanthropic organizations. And it’s really trying to provide something that all of us can benefit from.

So what is Open Humans trying to do? What is my idea on how to solve this problem?

Rather, if someone came up with another version of Open Humans that did it better, then they’d be solving the same problem, but this is the approach that I think works – or does things that are important.

And that is to center the data on the individuals.

And what do I mean by that?

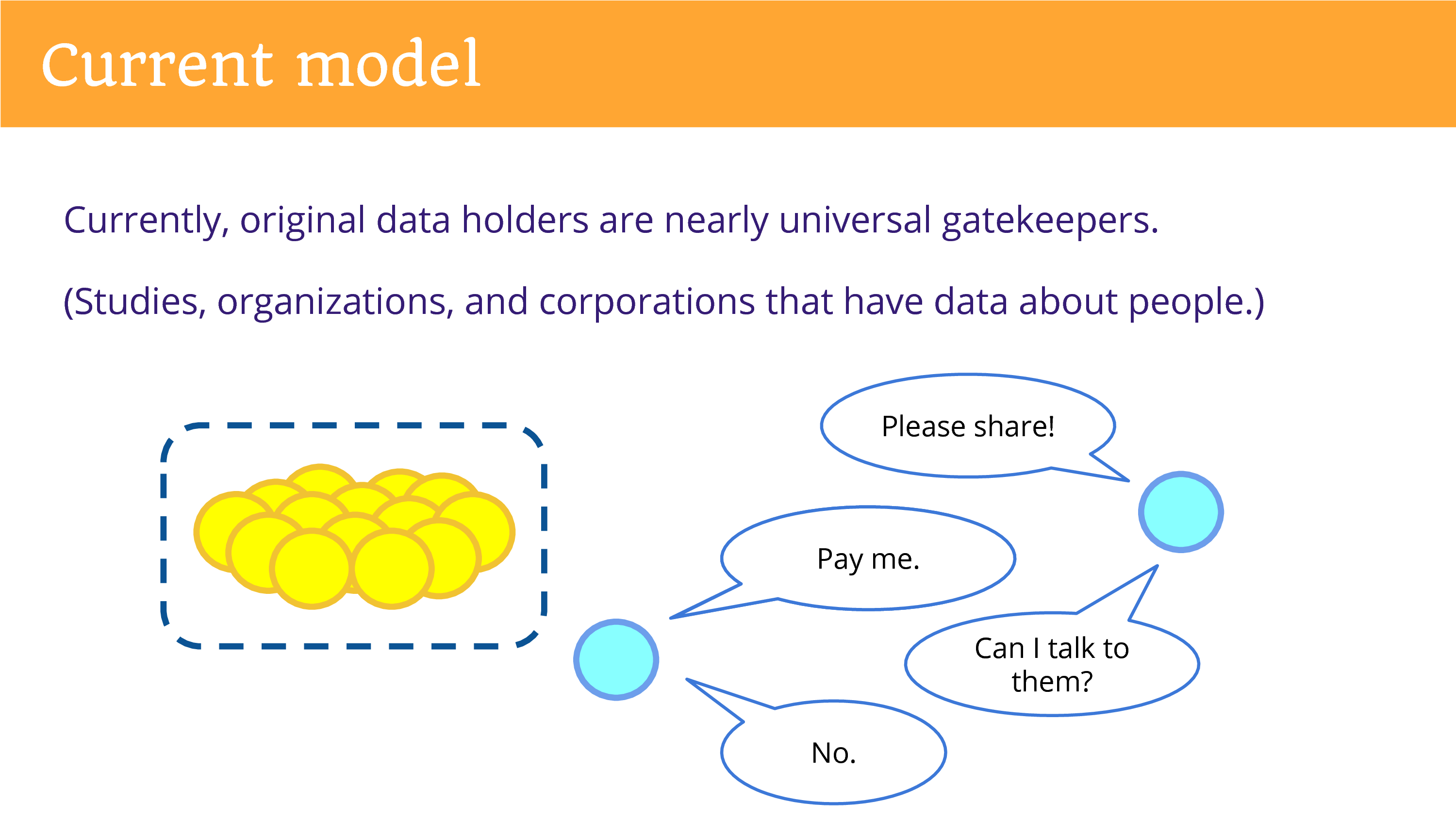

Well, in our current model, the original data holders are the nearly universal gatekeepers. That refers to diverse entities: the studies that produce data in research, and organizations, but also corporations that have data about people.

Well, in our current model, the original data holders are the nearly universal gatekeepers. That refers to diverse entities: the studies that produce data in research, and organizations, but also corporations that have data about people.

So, as someone from the outside, looking in, you find yourself going to this entity and asking them to share. One concern that is commonly brought up that they cannot, that it would violate privacy. Or they want to be paid.

And then you might find yourself with another question. The data’s not enough, you need to ask maybe a simple survey question to get at the information that you want, that you need to build on the data by engaging the individuals. And if you ask to do that, usually the answer is going to be “No”. The relationship is controlled by that entity.

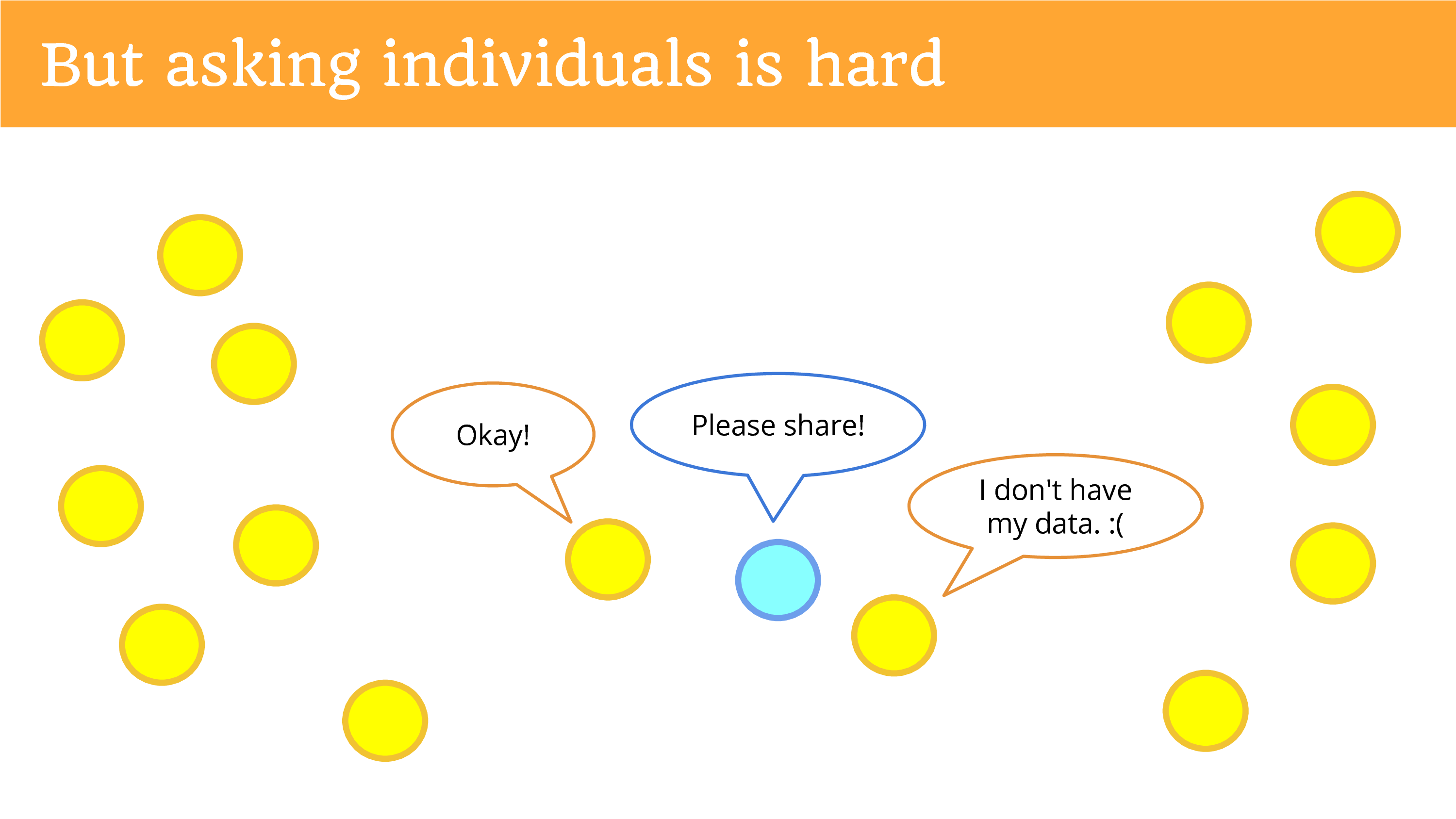

But asking the individuals is hard! You get out there, get on the sidewalk with a sign, asking them to donate to you. Most of them are not going to hear you. You can put your website up and ask for donations, ask people to share, and you might get one person to come by and say “Okay”.

But asking the individuals is hard! You get out there, get on the sidewalk with a sign, asking them to donate to you. Most of them are not going to hear you. You can put your website up and ask for donations, ask people to share, and you might get one person to come by and say “Okay”.

Another person will say they don’t have their data. That’s an ongoing problem. If you don’t have your data – the entity has it, but you don’t have it – so you can’t donate it. The entity’s the only data holder. Then you can’t ask the individual for it.

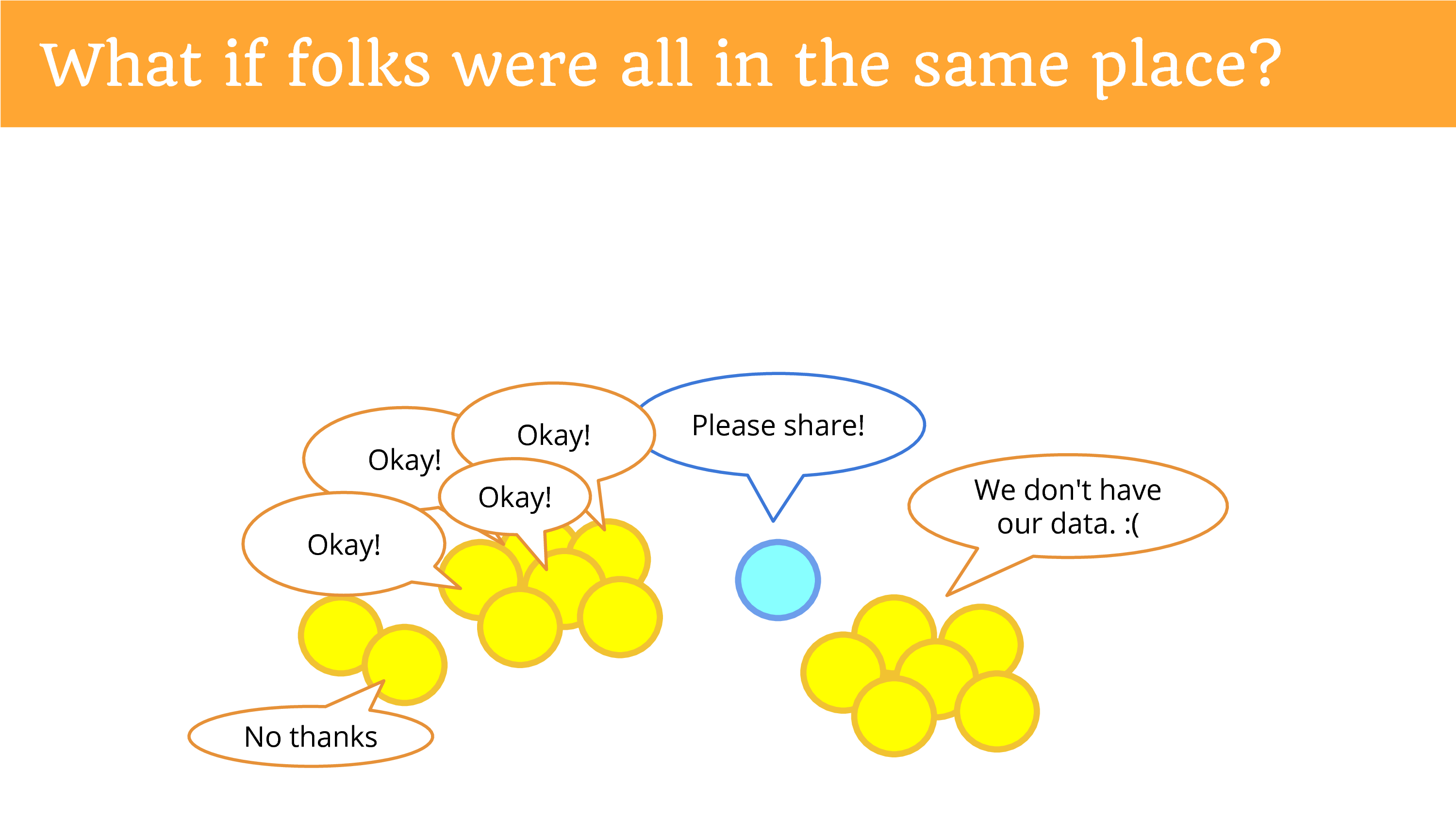

What if people were in the same place? So it became easier to ask them? If you said “please share” and they all heard you? And they said “okay”?

What if people were in the same place? So it became easier to ask them? If you said “please share” and they all heard you? And they said “okay”?

Except some of them might say “no thanks”. Because now we’re giving them the power to decide, and this issue of privacy is now under their control, and they can decide whether or not they want to share potentially identifiable and sensitive data with you. (There’s still the people who don’t have their data.)

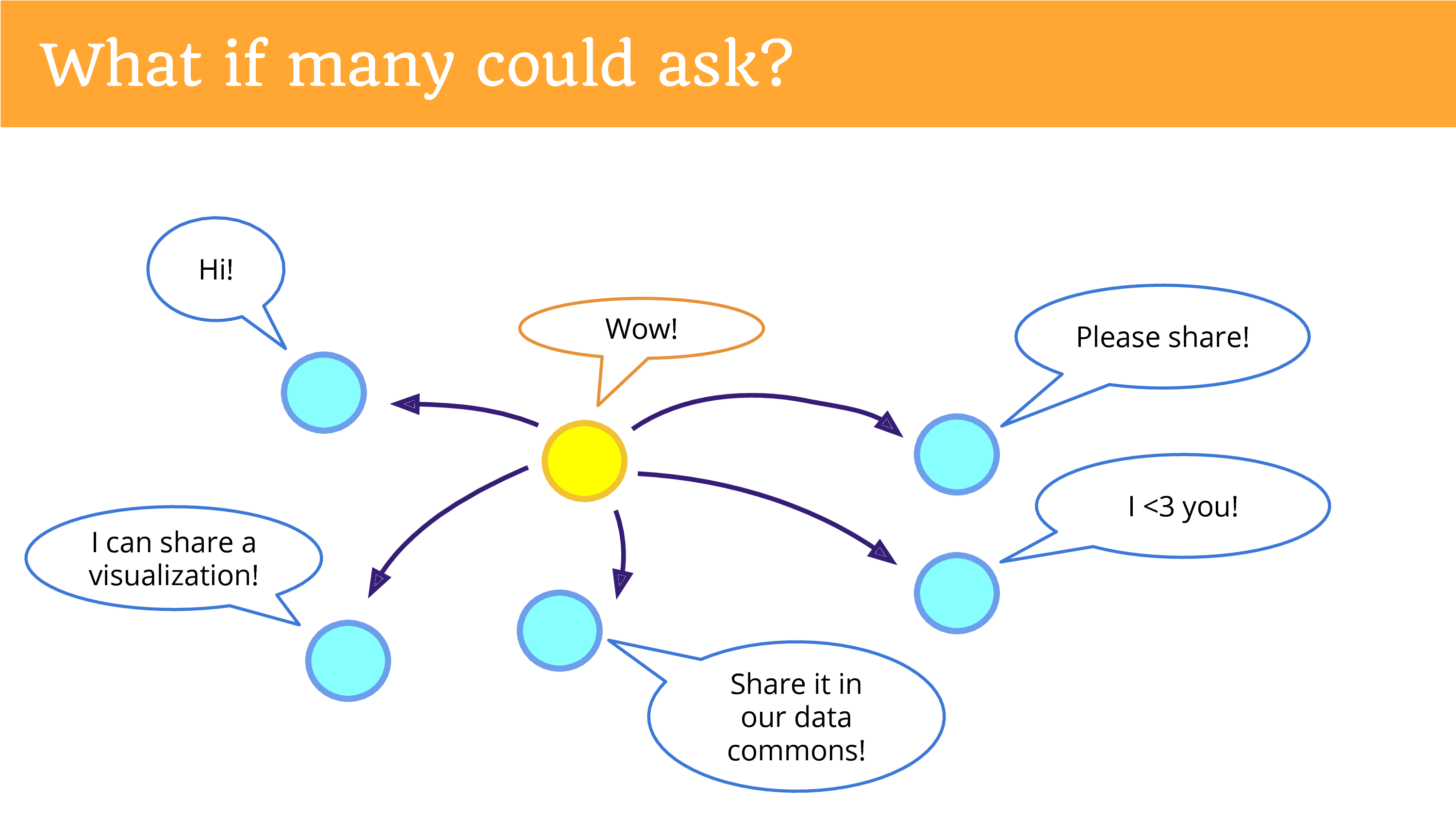

What if many could ask? What if one person could get re-used by many different projects? Data is not a zero sum game. It’s actually trivial to hit a button a couple different times and share it with all of those different entities.

What if many could ask? What if one person could get re-used by many different projects? Data is not a zero sum game. It’s actually trivial to hit a button a couple different times and share it with all of those different entities.

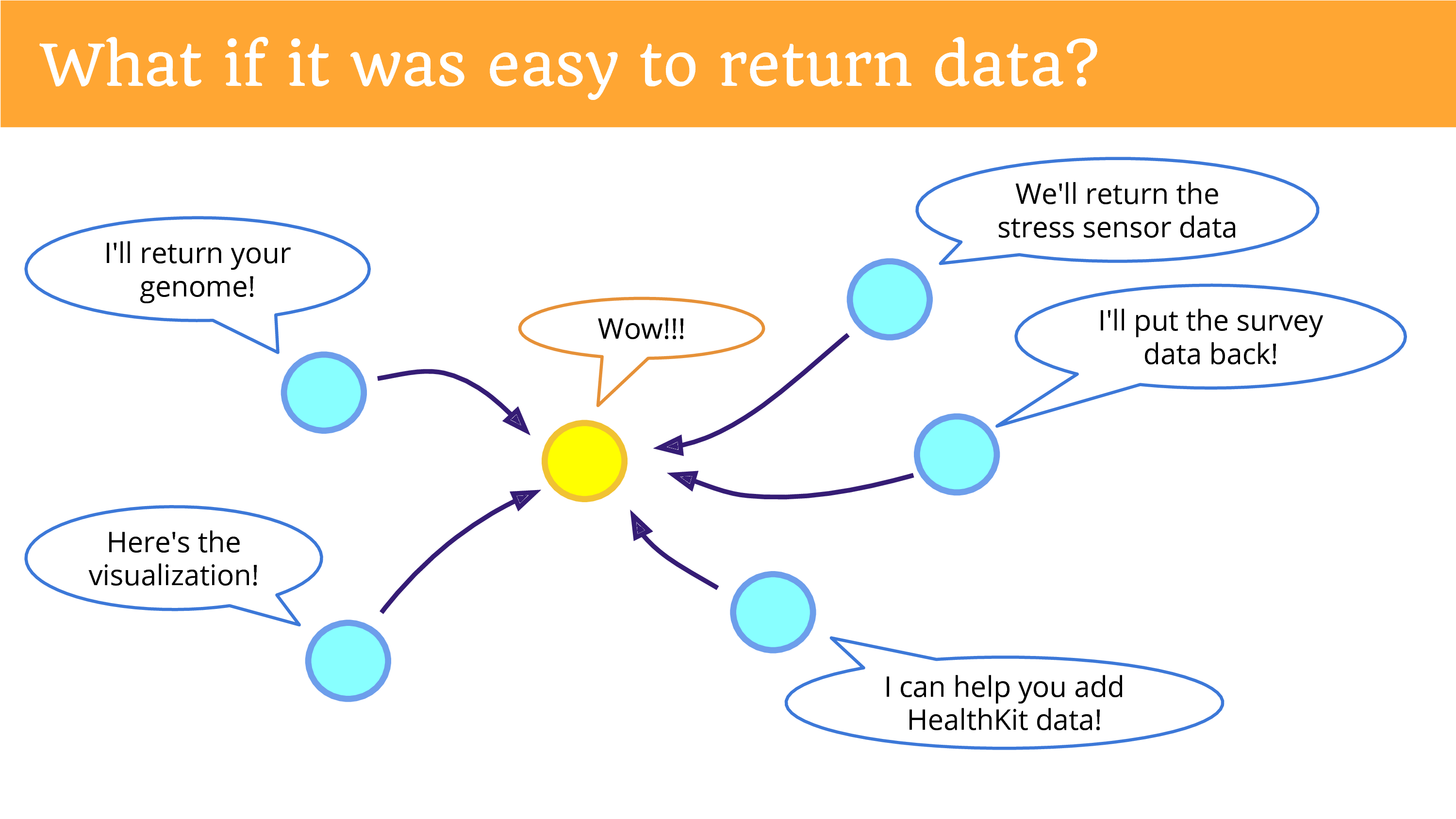

What if it was easy to return data? And this is what I really hope we can be doing more of. In the top left is something that’s not happening yet, but I hope you can see the potential now, if we were returning the data in a place, in a platform, a community that gives people the opportunities to re-donate it. That there’s potential for new research that we’re missing out on.

What if it was easy to return data? And this is what I really hope we can be doing more of. In the top left is something that’s not happening yet, but I hope you can see the potential now, if we were returning the data in a place, in a platform, a community that gives people the opportunities to re-donate it. That there’s potential for new research that we’re missing out on.

We also have the ability for people to create projects that just simply add a data source. So, step away from this concept of only having studies – but think about a citizen scientist who says: “Oh, I can help provide a data source that researchers can use.”

In fact one did. James Turner said: “Why don’t have HealthKit data?” And I said “We don’t have an iOS developer.” Because HealthKit data – it measures your steps by the way, if you have an iPhone, your steps are being measured – it’s all being stored on the phone. It’s not in the cloud. That’s how Apple is protecting its privacy, you need to install an app to get it off. He writes an app to put the data into Open Humans. And a researcher later used it, a master’s student at ASU.

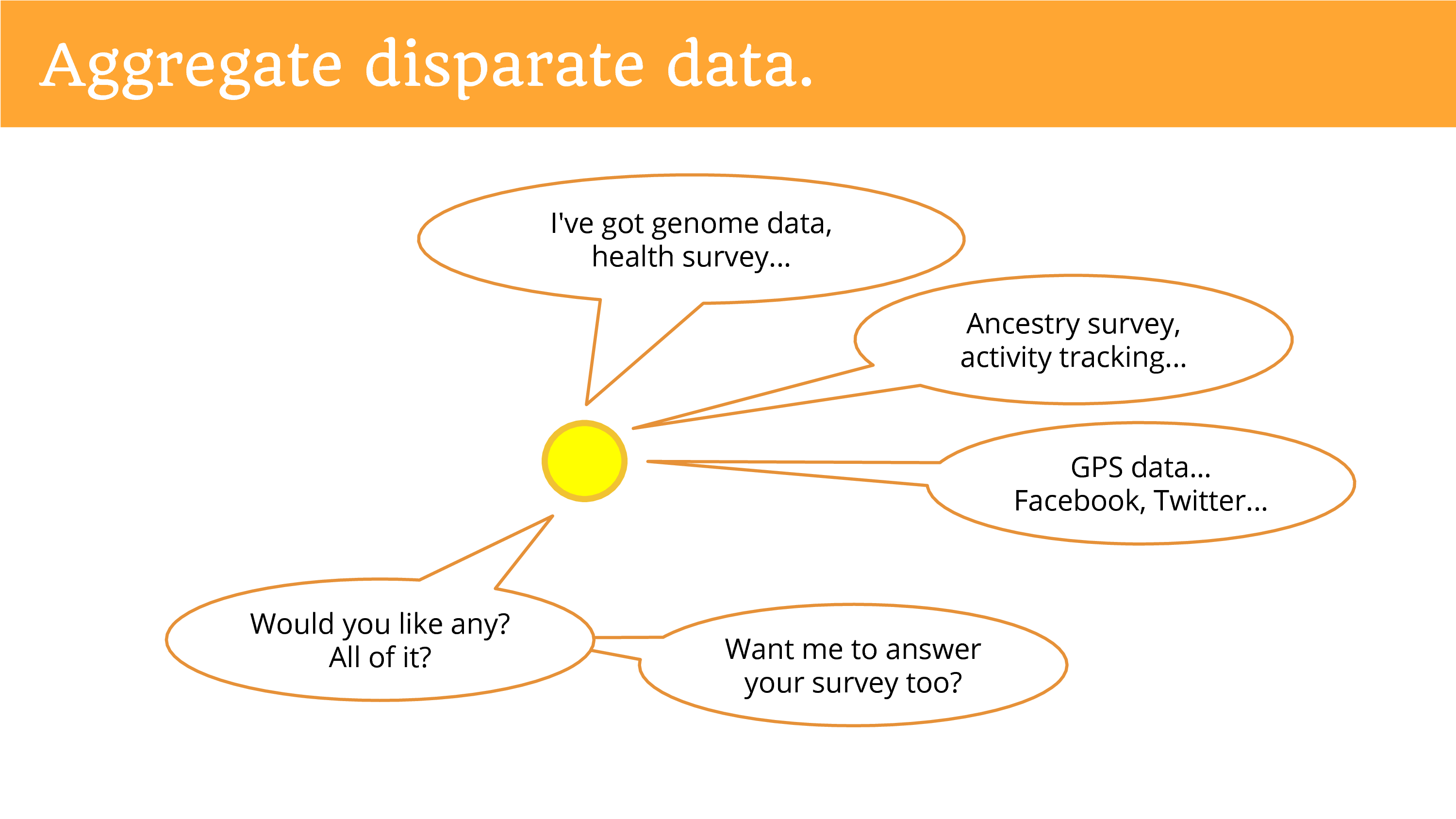

We can aggregate disparate data around people. So when you’re talking about getting data from a primary data holder, they just have their data. But when you talk to the individual they can connect data from disparate sources. And so now you can achieve that dream, of multi-faceted data. Of the genome, and the health, the ancestry, activity tracking, GPS, maybe social media feeds. It’s really what you can imagine at this point.

We can aggregate disparate data around people. So when you’re talking about getting data from a primary data holder, they just have their data. But when you talk to the individual they can connect data from disparate sources. And so now you can achieve that dream, of multi-faceted data. Of the genome, and the health, the ancestry, activity tracking, GPS, maybe social media feeds. It’s really what you can imagine at this point.

And the person can offer to give it to you. And they can offer to do more with you.

You can engage them and ask them to fill out a survey. The way Open Humans is constructed, we are giving you the relationship with the individual, and not merely the data. That relationship occurs via an anonymous identifier, so you can actually conduct all of your research more securely by not receiving their email address or their name. Maybe the data is potentially identifiable, but for god’s sake, if you have someone’s email address attached to it, it’s pretty identifiable.

The ability to receive donations, and ask people to go answer surveys, or otherwise engage with you – is a powerful thing. And that’s something that’s lost when we talk about sharing the data through the central data holder.

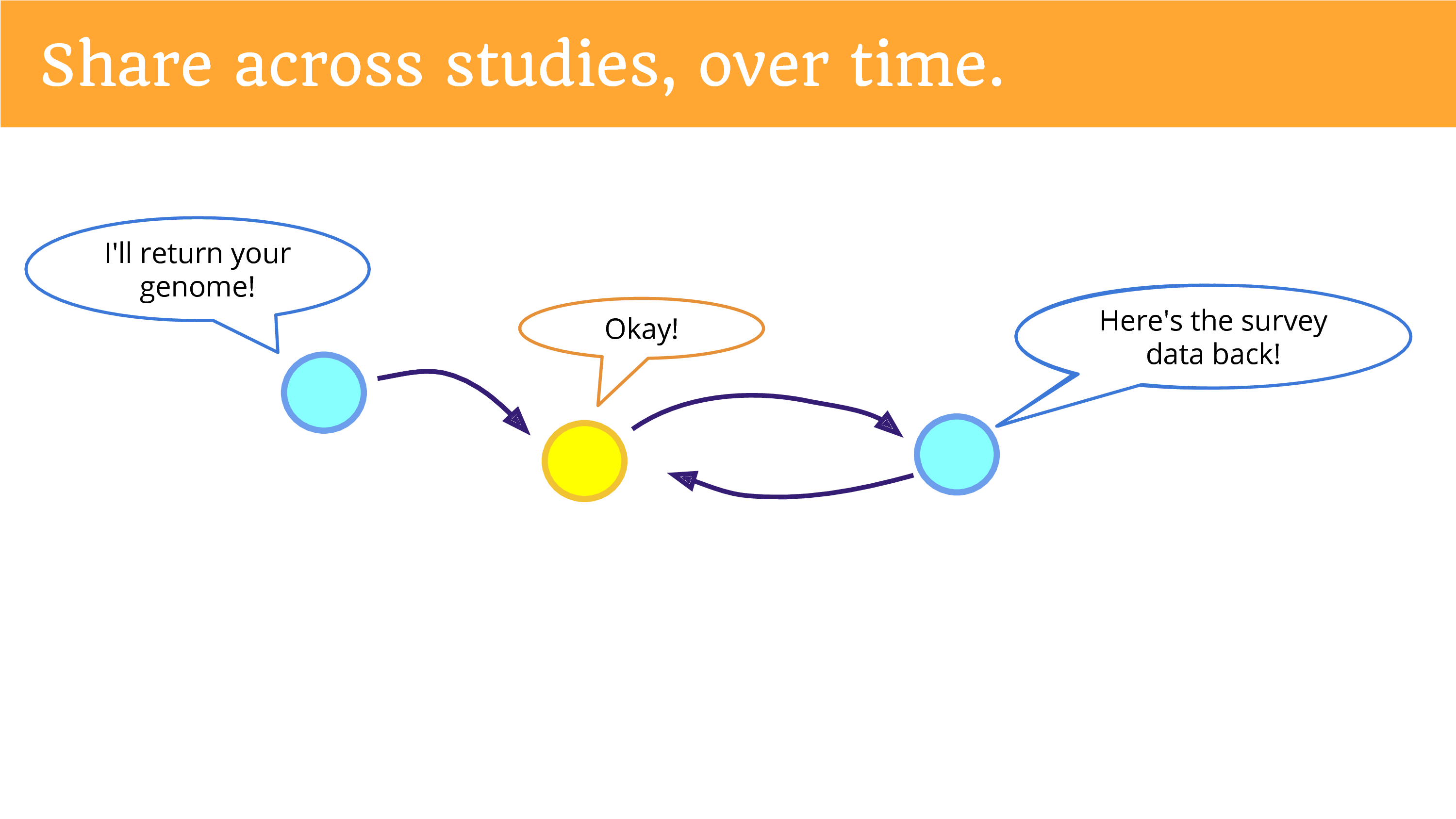

Finally, we can share data across studies, over time. We can think of this as a sort of “open cohort” that is shared between studies. So, one study that returns data… means that another study may come along and say “Can I see that data, and add to it, and build upon it?” And that data can be shared… and of course that study can give information back. Put the survey back. I don’t know if you’ve engaged in research as a participant, but the surveys can get kind of annoying over time. So maybe if you put the survey data back, another study won’t have to ask the same questions again? One can hope, one can hope. I think that it’s likely that we’ll still get lots of surveys.

Finally, we can share data across studies, over time. We can think of this as a sort of “open cohort” that is shared between studies. So, one study that returns data… means that another study may come along and say “Can I see that data, and add to it, and build upon it?” And that data can be shared… and of course that study can give information back. Put the survey back. I don’t know if you’ve engaged in research as a participant, but the surveys can get kind of annoying over time. So maybe if you put the survey data back, another study won’t have to ask the same questions again? One can hope, one can hope. I think that it’s likely that we’ll still get lots of surveys.

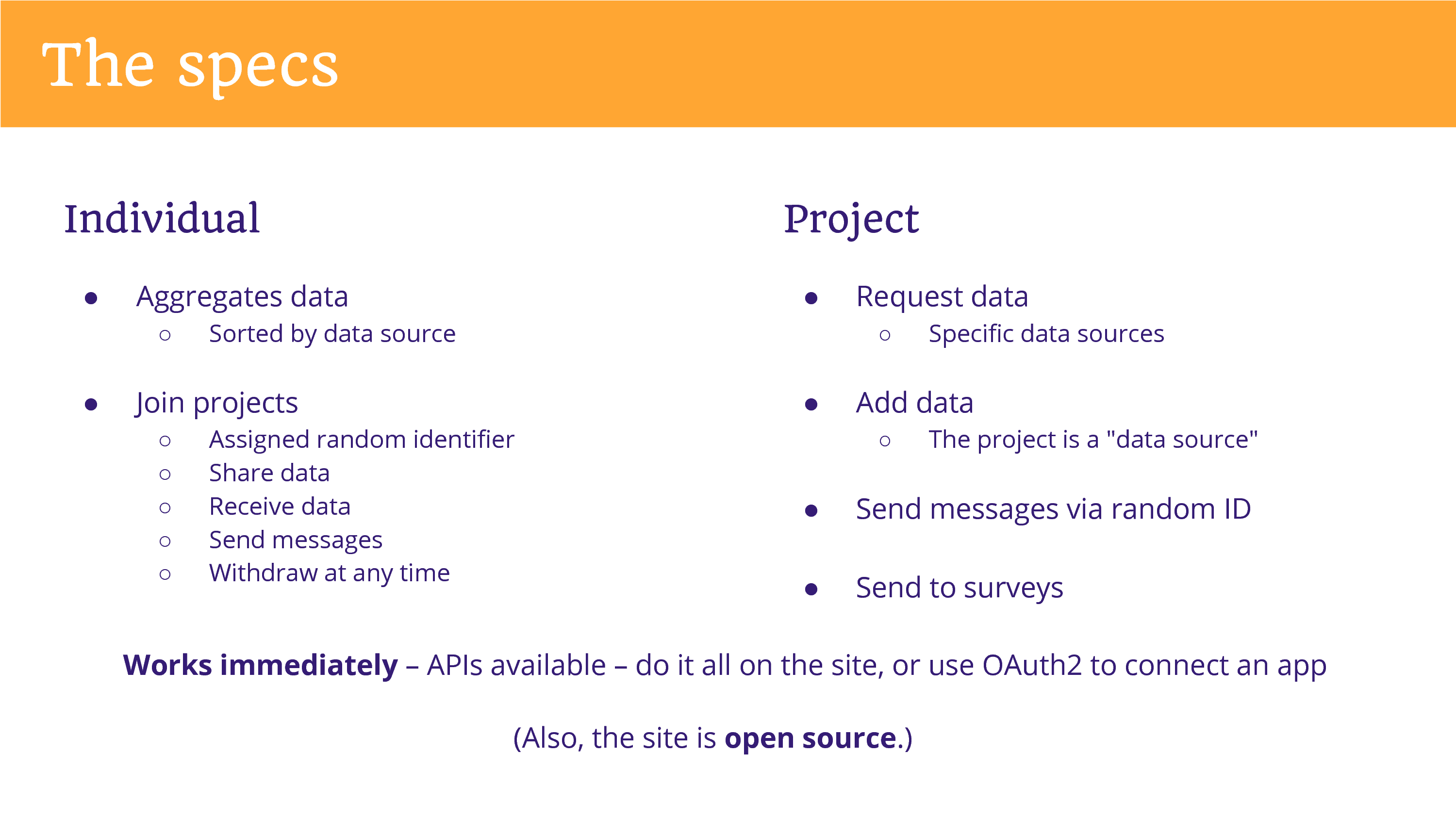

But to get at the specs, since you’re a programming crowd… I am also a programmer. I manage the full stack of this website. The individual is aggregating data, and it’s sorted by data source. When they join a project they’re assigned a random identifier. They are granting permission to share data that the project has requested, and they receive data if the project chooses to return data – that’s not required – neither is required. They can send messages to the project, and they can withdraw at any time. So they can hit a button and the project no longer has access to their data. Now, can I force a project to delete data? That’s going to be down to the project’s policies. Maybe some projects will say it’s not practical.

But to get at the specs, since you’re a programming crowd… I am also a programmer. I manage the full stack of this website. The individual is aggregating data, and it’s sorted by data source. When they join a project they’re assigned a random identifier. They are granting permission to share data that the project has requested, and they receive data if the project chooses to return data – that’s not required – neither is required. They can send messages to the project, and they can withdraw at any time. So they can hit a button and the project no longer has access to their data. Now, can I force a project to delete data? That’s going to be down to the project’s policies. Maybe some projects will say it’s not practical.

The project can request data, add data, send messages, send to surveys. Importantly, this is all working immediately – this is all set up and it works immediately – there’s APIs available. Do it all on the site, or use OAuth2.

The site is open source.

I got asked this in my application. Is your software open source? Well yes, it is.

But I could have built a website that asks for data donations, and put it into a hole where nobody could get it. That’s not the purpose, that’s not the type of open here. So the “open-sourciness” of this site is a little bit beside the point, the “open-sourciness” of this project is about how you can work with people and their data.

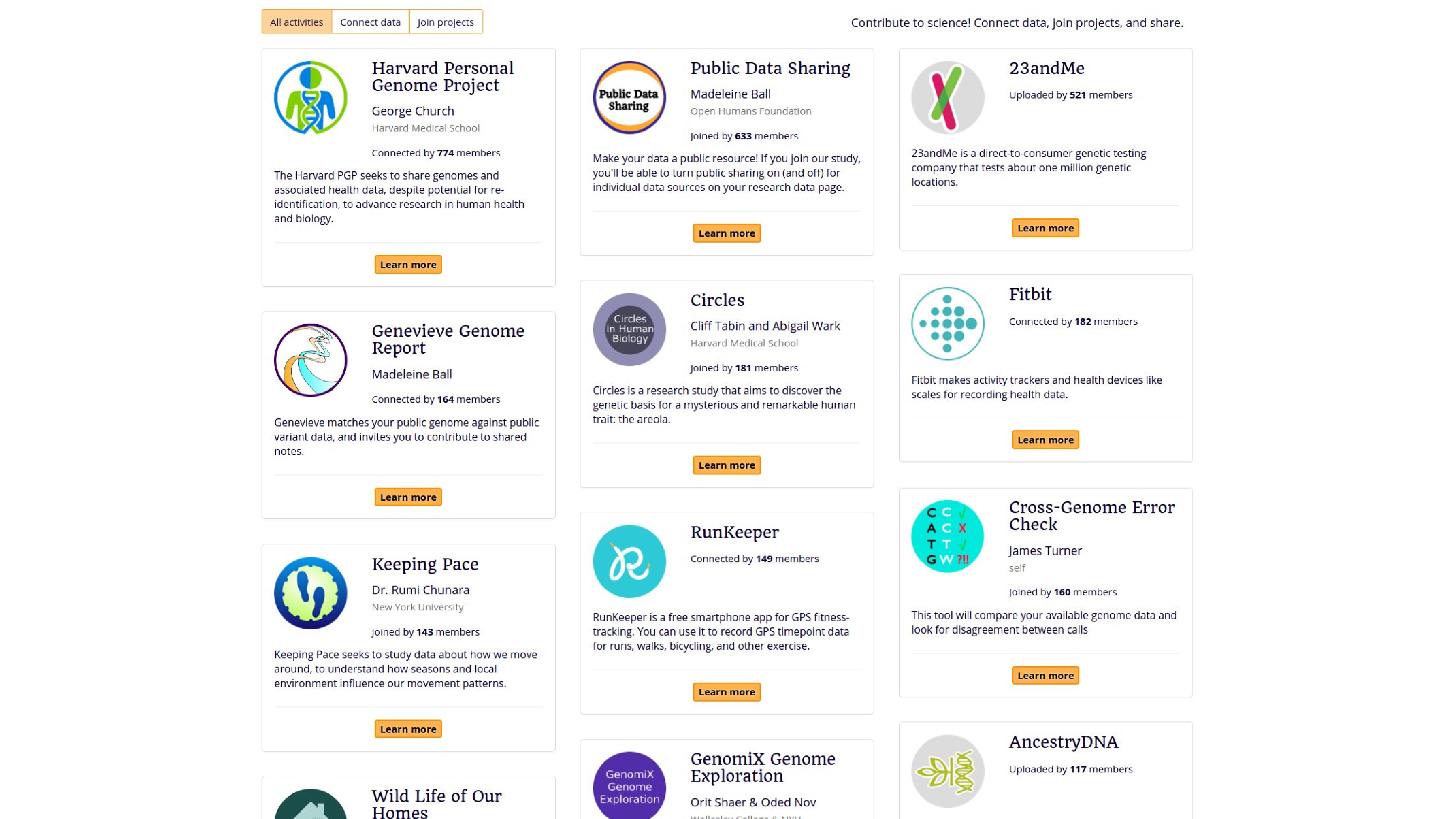

So here’s some things, examples of projects, the activities that people can do. They can bring in their data from the Personal Genome Project, from 23andMe, from Fitbit. They can also contribute it to studies, like Keeping Pace, which is looking at GPS data. There’s also some analysis tools, like the Genevieve Genome Report, or James Turner also added Cross-Genome Error Check.

So here’s some things, examples of projects, the activities that people can do. They can bring in their data from the Personal Genome Project, from 23andMe, from Fitbit. They can also contribute it to studies, like Keeping Pace, which is looking at GPS data. There’s also some analysis tools, like the Genevieve Genome Report, or James Turner also added Cross-Genome Error Check.

Now I’m going to revisit the idea of a public data model, and contrast with this idea of sharing… the multi-faceted ability to share with projects.

This is me trying to challenge someone in the audience that’s already a sharer. Bastian is already sharing his genetic data.

Bastian, would you be willing to share your location data? The continuous location data passively tracked by your phone over the course of years?

Yeah? You would?

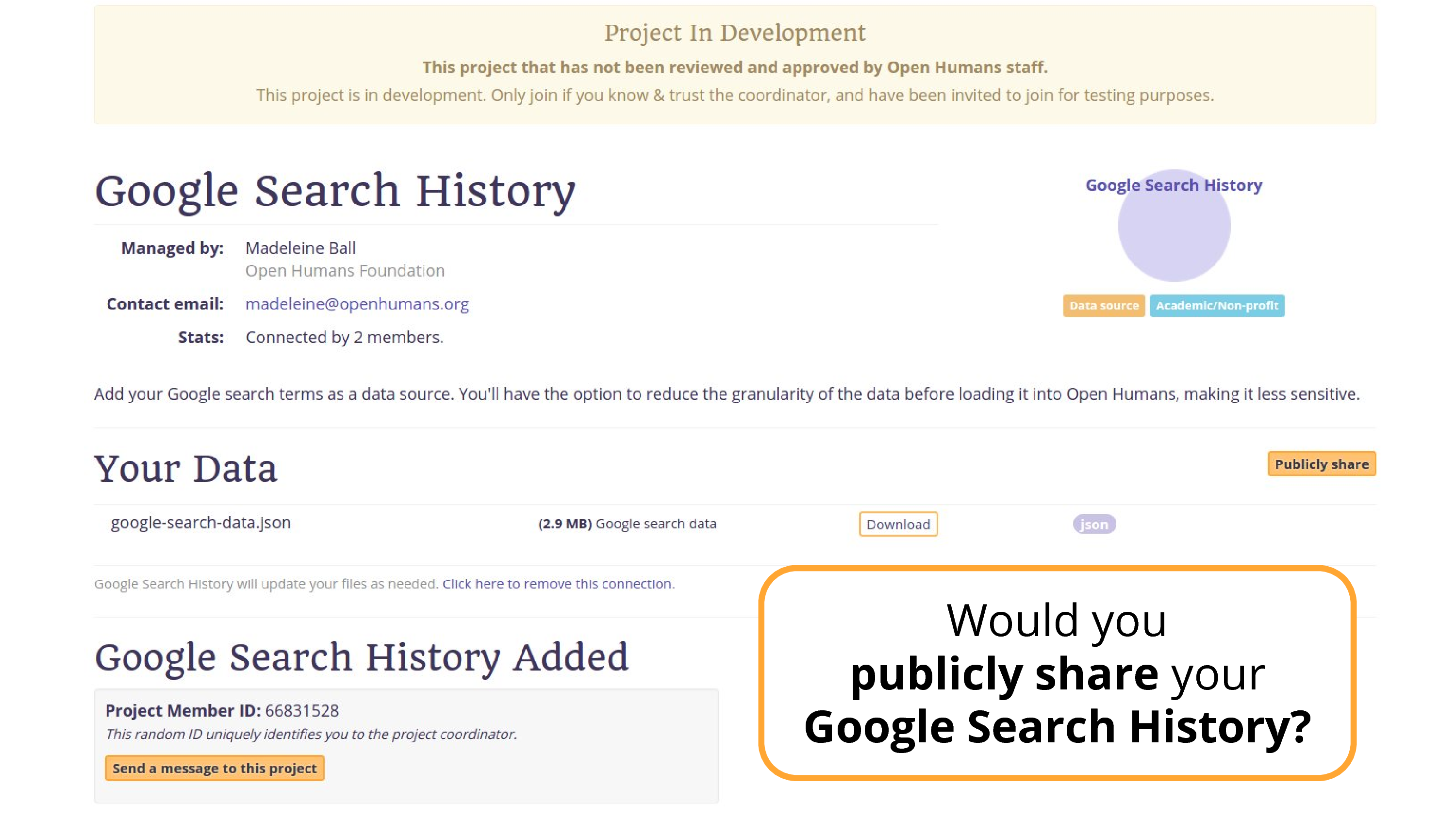

Well, what about this data source that I’ve been working on.

Well, what about this data source that I’ve been working on.

This is… Google Search data.

[laughter]

No?

There’s always going to be some type of data that’s just going to go a little bit too far for you.

So this dream, that people are just going to open source themselves. That they’re just going to relax and let all of their data be seen by everyone… we’re going to be able to find something that you’re not going to want to share publicly.

So it’s not always the solution. That’s what I’m trying to get at.

Still a great solution. If I go back, you’ll see there’s a publicly share button, in theory someone could publicly share this data. There are people publicly sharing their location data. Only a very few.

So now I want to bring this to a concrete example. I’ve talked abstractly about what could be done, what’s possible. Well, this is a concrete example of using this system, that’s actually being done by a patient advocate and citizen scientist and general all-around badass – and I think this is how it’s getting used first, because academics are a little slower, they want to get a proposal together, and funding lined up, and then eventually… maybe a year later… something will happen.

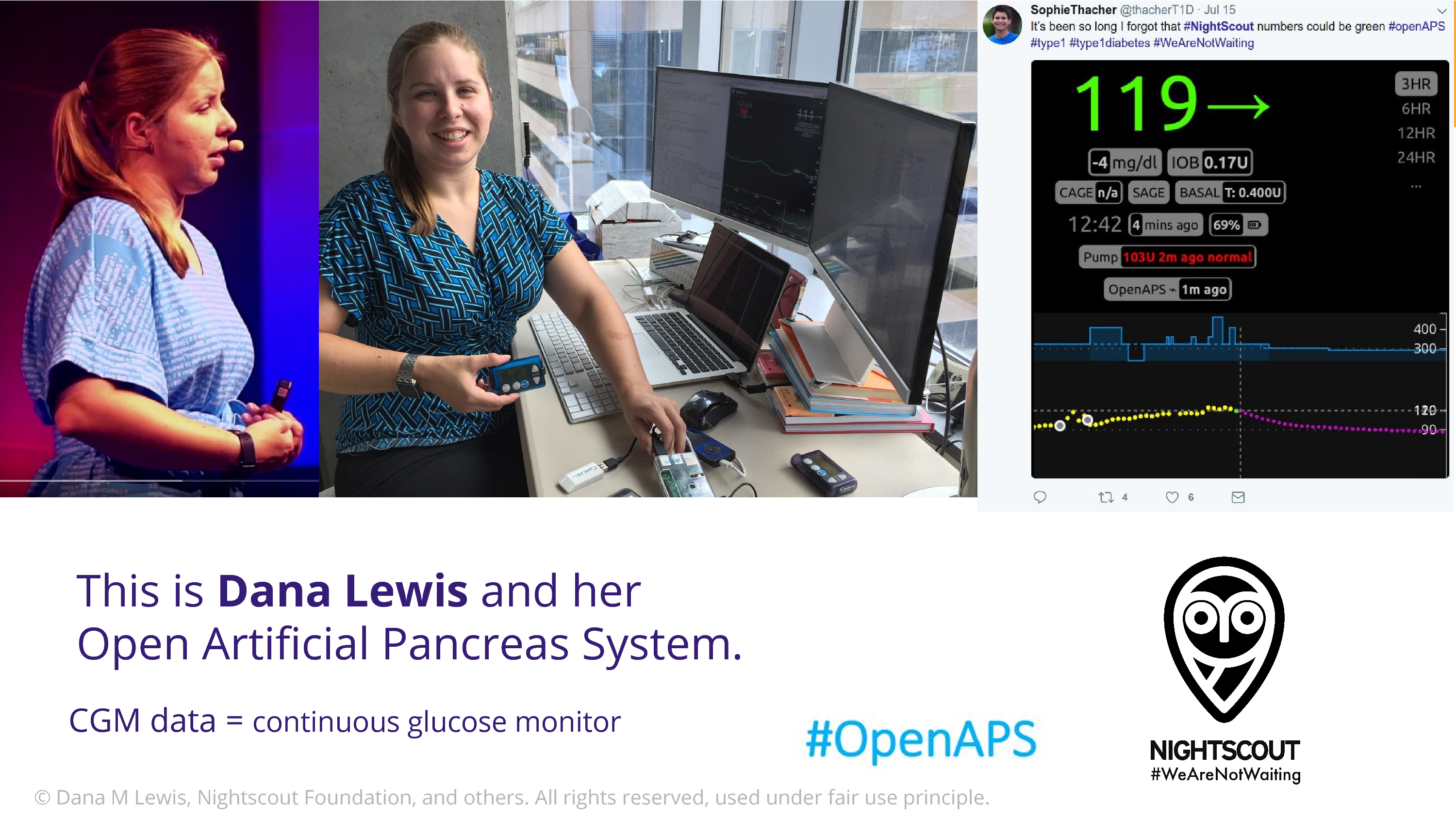

This is Dana Lewis. Does anyone in the audience know who Dana is? Well, Bastian does because I talk about her. I’m so excited to talk about Dana to this crowd.

This is Dana Lewis. Does anyone in the audience know who Dana is? Well, Bastian does because I talk about her. I’m so excited to talk about Dana to this crowd.

Dana comes from a community of open source developers that are type 1 diabetic patients and their caregivers. And they have figured out how to get into their data stream. There are devices that continuously monitor glucose data. And they discovered ways to empower themselves with that. The Nightscout Project takes that data, which is in the cloud – the first step is to get the data into the cloud – and then Nightscout iterated on this to put in on a webserver so you can remotely log in and look. And the Nightscout users are 90% parents who want to be able to look at their child’s glucose when they’re not able to be there, when they’re in school.

Dana has type 1 diabetes, and she had a problem. She’s a heavy sleeper.

I didn’t know this before working with this community but type 1 diabetes patients – are there any type 1 diabetes patients in the room? Well type 1 diabetes patients have a 1 in 20 lifetime risk of dying in their sleep. Due to hypoglycemic coma. So this device, it has an alarm that goes off when your blood sugar getting low. But Dana’s a heavy sleeper, and she was not waking up with this alarm. And that’s a very scary situation. Well, she has access to the data. So Dana and Scott put together some software to get a louder alarm.

All of this software is open source, this is a thriving, vibrant open source community. It’s patients helping each other, so there’s people wandering in who have no clue what to do, and others who are helping them to learn Heroku, to set this up.

Once they’d done that, Dana and Scott realized that Dana’s also wearing an insulin pump, a basal insulin pump, that’s operated via bluetooth. And they thought, we can connect these. We can close the loop. We can build an algorithm that goes from the glucose data, to adjust what the insulin is putting in, and they did that. And formed the OpenAPS community. One of the things I love about Dana is that she’s really pushing this. This is now in the realm of medical device territory. That’s her code on her shirt, on the left there. She’s in the US, and she’s using the fact that this is free speech to defend her right to share the source code.

Well, the opportunity here is that the glucose data is being collected, and how can we collect this to use it for research? How can we aggregate it, how can we manage data sharing and enable community research?

Well, the opportunity here is that the glucose data is being collected, and how can we collect this to use it for research? How can we aggregate it, how can we manage data sharing and enable community research?

The solution is to use Open Humans.

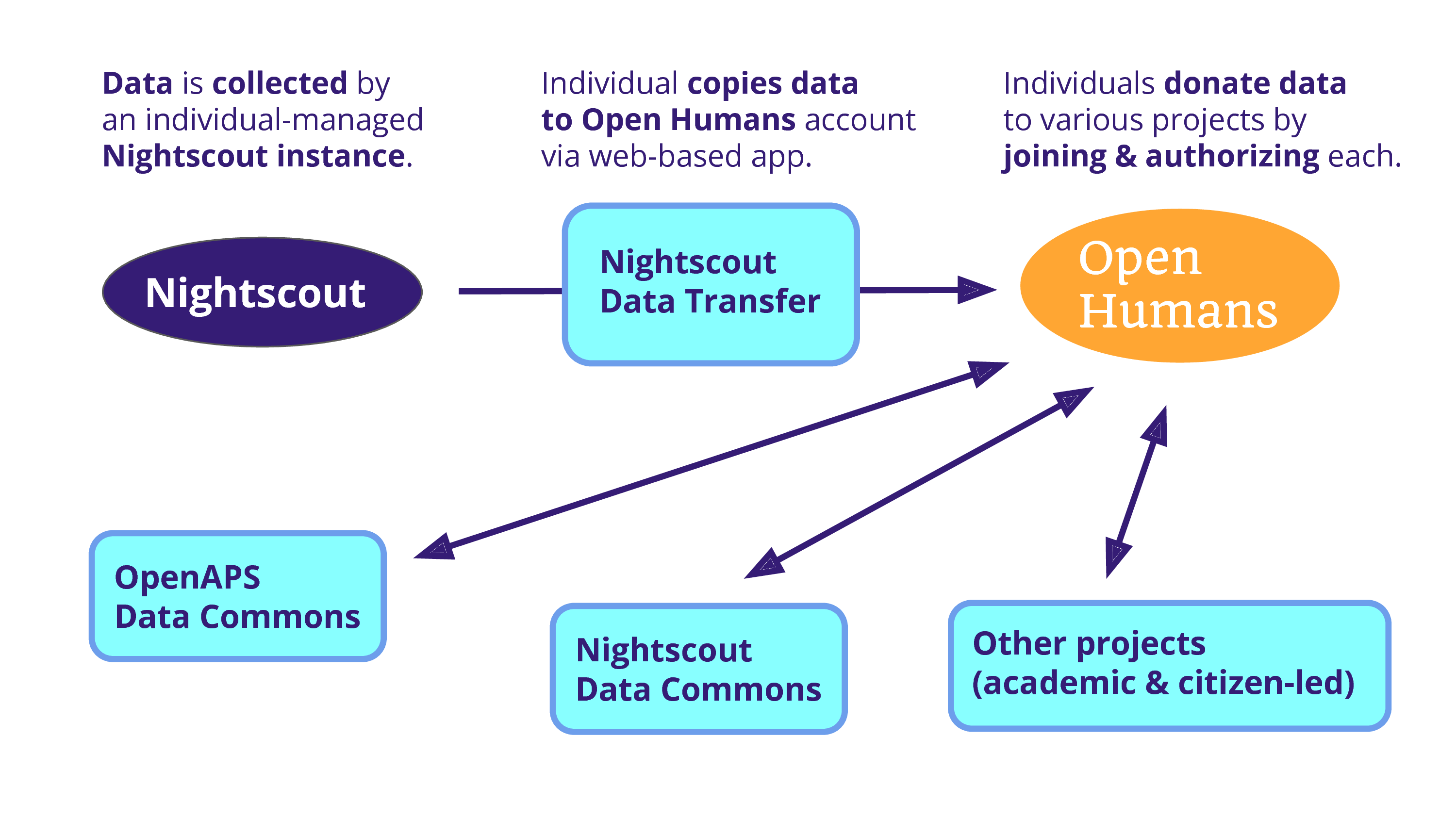

And the problem is that data is being collected on an individual scale. And so, Open Humans becomes a solution because we can use a project – as a data source – to copy that data into an Open Humans account. From there, an individual can donate it to various projects, including one that Dana is running: the OpenAPS Data Commons. There’s also a Nightscout Data Commons that we’re hoping to launch soon, and there’s the potential for various other projects that are both academic and citizen-led.

And the problem is that data is being collected on an individual scale. And so, Open Humans becomes a solution because we can use a project – as a data source – to copy that data into an Open Humans account. From there, an individual can donate it to various projects, including one that Dana is running: the OpenAPS Data Commons. There’s also a Nightscout Data Commons that we’re hoping to launch soon, and there’s the potential for various other projects that are both academic and citizen-led.

Dana’s data commons demonstrates a sort of middle tier in which data donation can occur, that’s not public, but is granting multiple uses. And Dana has brought this data to researchers at Stanford and at Johns Hopkins, and they’ve started analyzing it. And it’s the type of data where you only need like 20 people to establish significance, because it’s such a dramatic sort of thing.

So as I close, as I get near the end, I want to say something about why I’m here.

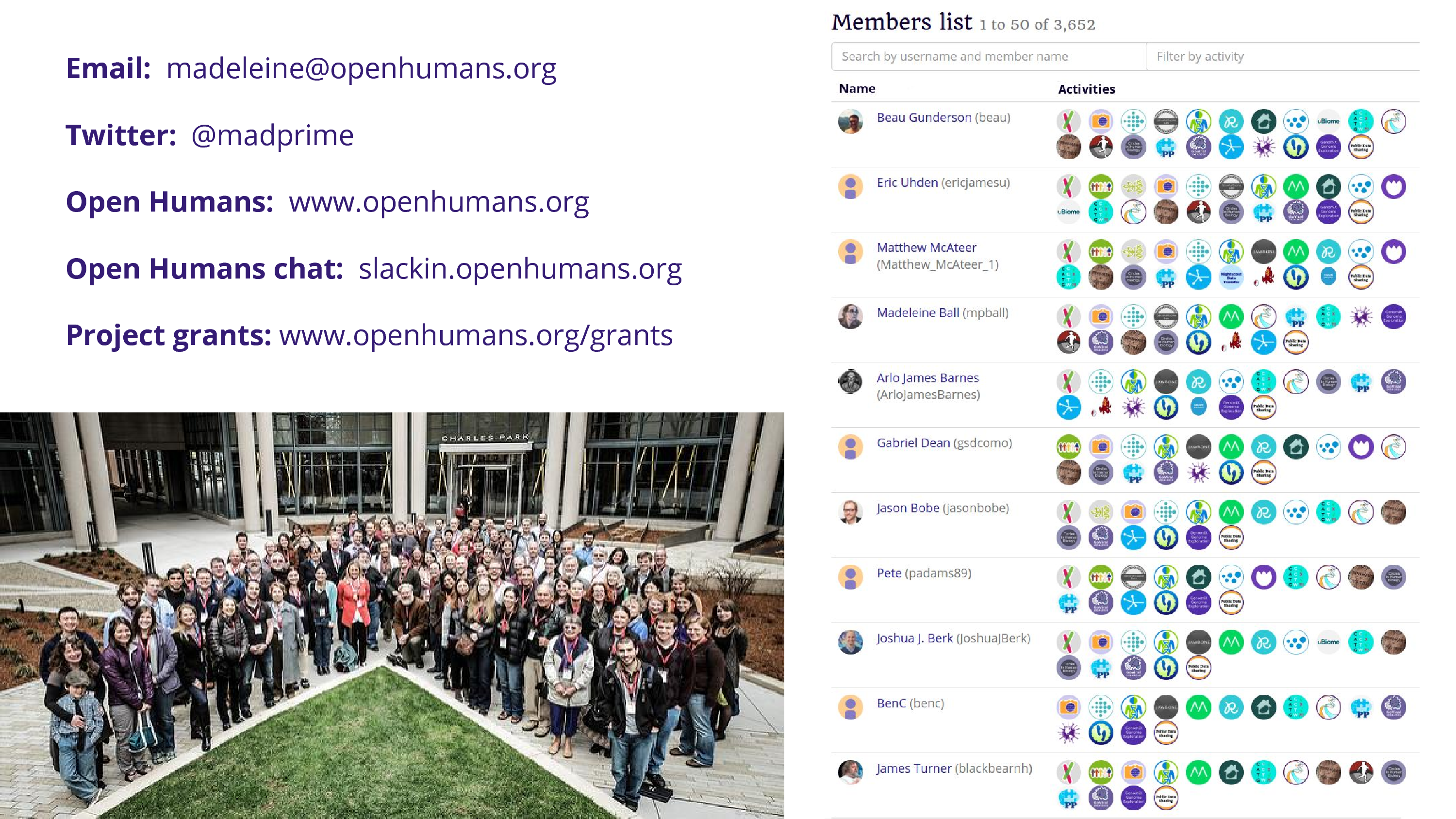

I want to invite everyone to help build this. This is a type of community and platform that can only exist when people buy in together and decide to make projects on it, because each project feeds forward and helps other projects to exist. To that end, I’m putting forward grants of up to $5000 for projects on the site that will help. And so if you have any idea of something cool to do with this data, that would help grow this ecosystem, or if you know anyone who might be interested – maybe on like the grad student level, because this is not a huge amount of money, it’s Google Summer of Code money – then by all means share this with them. I also have need for a developer, so if you go to the bottom of the website, you’ll see a jobs posting…

I want to invite everyone to help build this. This is a type of community and platform that can only exist when people buy in together and decide to make projects on it, because each project feeds forward and helps other projects to exist. To that end, I’m putting forward grants of up to $5000 for projects on the site that will help. And so if you have any idea of something cool to do with this data, that would help grow this ecosystem, or if you know anyone who might be interested – maybe on like the grad student level, because this is not a huge amount of money, it’s Google Summer of Code money – then by all means share this with them. I also have need for a developer, so if you go to the bottom of the website, you’ll see a jobs posting…

But another thing I want to tell you is that I want your feedback. Tell me what’s not so great, or what could be improved. I’m really genuine in my desire for this potential solution to be something that others buy in and have feedback on. To that end, there’s a chatroom, I want to invite you to give feedback – I’m sharing the chatroom with you because you could give me private feedback and I could ignore it, right, and nobody would know. But here’s a chatroom where you can tell me, and tell everybody else, and if you think I’m doing something wrong, everybody’s going to know. I’m exposing myself here to the community talking to each other, and giving me feedback on how they should operate – we should operate – this should be something that’s ours.

So what does open mean. This is a closing remark as I back out, when I think about “what does open mean to us”.

A lot of times when we approach the concept of open, we think in terms of quality and efficiency. So we’re thinking about making science more reproducible. Or we’re thinking about not re-inventing the wheel, on re-using work that others have made. And this is a great type of open. This is much more fundable.

A lot of times when we approach the concept of open, we think in terms of quality and efficiency. So we’re thinking about making science more reproducible. Or we’re thinking about not re-inventing the wheel, on re-using work that others have made. And this is a great type of open. This is much more fundable.

But another type of open, that kind of hearkens to the roots of open source – to the experience of Stallman as he was frustrated with his printer, and wanted to fix it, and he wanted the source code to that – is the type of open about access, and empowerment, and growth.

But another type of open, that kind of hearkens to the roots of open source – to the experience of Stallman as he was frustrated with his printer, and wanted to fix it, and he wanted the source code to that – is the type of open about access, and empowerment, and growth.

Because when we enable people to do new things that weren’t previously possible, more people to do things that they previously couldn’t have done, then we can see things happen that wouldn’t have happened before. And this is harder to predict, but I think really beautiful. And so we can hope for data sharing that would not have otherwise happened. We can hope for types of research that were not previously possible.

So. Last slide. I want to thank the participants in the Personal Genome Project and the members of the Open Humans community. Open Humans is not a study in itself, I think an IRB would choke on that. It’s a nexus point, a matchmaker. And up there in top left, some contact information for me, and that chatroom again. And I think with that, I’ll open it up for questions.

So. Last slide. I want to thank the participants in the Personal Genome Project and the members of the Open Humans community. Open Humans is not a study in itself, I think an IRB would choke on that. It’s a nexus point, a matchmaker. And up there in top left, some contact information for me, and that chatroom again. And I think with that, I’ll open it up for questions.